The Wheel Of Consent

By Michael Dresser

In the current #metoo environment, consent is something that has become a hot topic – we all know it’s important, and we all know there can be heavy repercussions for getting wrong. Consent is something we don’t get taught – but yet we’re increasingly expected to know how to do it right.

Sex and intimacy can be a minefield to navigate and stay safe – both physically and emotionally.

And most of us will be carrying trauma from growing up in a society which often tries to repress or contain our authentic expression of who we are and what we want.

So what is consent, and what does it mean?

In the midst of all this confusion, and damage, it can be really hard to know what to do – or not do!

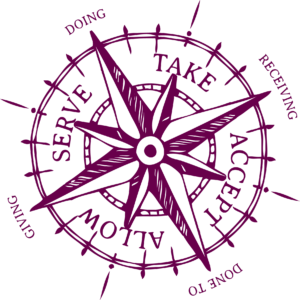

As an intimacy coach I work using an approach called the Wheel Of Consent – a simple, powerful navigational tool that brings clarity and choice to our interactions with others, and can revolutionise the relationship we have with our own self, as well as with partners, lovers, family, friends, and even work colleagues!

It’s also a great way to start to pick apart some of the patterns of giving, receiving, doing and being done to that most of us have never even thought about.

It’s not just about sex

We’ve become used to hearing about consent in terms connected with sex – particularly rape, and sexual assault. And mostly it’s talked about in terms of saying ‘yes’ or saying ‘no’. But real life is rarely quite that simple.

True consent is not simply about one person saying yes. Consent is the agreement between two or more people about what will or won’t happen, and – just as importantly – the understanding of who it is for.

It’s a fundamental life skill which goes way beyond the bedroom!

Sex can be a challenging experience for most of us, for lots of reasons, and this can often be compounded by experiences of shame about our bodies or attractions. Not – perhaps – the best environment in which to be trying to figure out where our limits and boundaries are.

So if we can learn what consent feels like – for our individual self – in contexts which are more simple and straightforward, then it becomes easier to trust our ability to be consenting when we feel vulnerable. In other words we can learn how to have consent in the bedroom by learning how to have it everywhere else too.

What are the key elements of a process of consent?

- Understanding what it is you feel – trusting your instincts, and – just as importantly – valuing what you notice;

- Communicating what you want – making an agreement with another person (these can come in all sorts of shapes and sizes);

- Doing what you enjoy – crucially both people in any interaction need to be comfortable with what’s happening – if you’re putting up with something you’re probably not fully consenting.

Crucially, at each stage, consent is really about choice: your choice to engage – or not to engage – with something or someone. And this includes allowing yourself choice to change your mind. Just because something feels good right now doesn’t necessarily mean it still will in five minutes, or tomorrow; just because you asked for something you usually enjoy doesn’t mean there’s something wrong with you if you’re not enjoying it right now.

To hug or not to hug

So how does this all work when we take it into everyday experience?

Consider how many times you’ve ended up in a hug with someone, when you hadn’t asked for it. Even if the other person does ask, the question is often a formality and they’ve started the hug before you’ve even had a chance to respond.

Because we live in a culture where it’s considered rude to refuse a gift that someone appears to be offering, most of us will go along with that hug whether or not we actually want it.

So then who is this hug really for?

Breaking it down four ways

Look at this picture of a hug – are you able to tell who it’s for?

(Illustration by Karolina Zolubak Instagram: @zoluart)

Now picture yourself as one of the people in that hug, and consider these different scenarios:

- I put my arms around you, serving you the kind of warm embrace you enjoy. (You are getting what you want).

- I wrap myself around you, my arms taking the hug I need. (I am doing what I want).

- I allow you to put your arms around me. (I am doing what you want).

- I accept your arms around me so you can hold me just the way I like it. (You are doing what I want).

The hug still looks the same, but the intention, and the experience, will be very different for each person in the hug in each scenario. And it will be different again if one person is not in agreement with what’s happening.

So tell me what you want, what you really, really want…

This is where the Wheel Of Consent comes in – it can help us become more aware of, and connected with, the subtlety of we want. It’s essentially a practice in taking apart giving and receiving – doing only one of them at a time. By practicing this way you experience interactions and learn things about yourself that you wouldn’t be able to access if everything was happening at once.

It’s based on the four different ways of engagement outlined above – otherwise known as the four Quadrants. Here’s how each one works:

SERVING – I put my arms around you, serving you the kind of warm embrace you enjoy. You are getting what you want.

Traditionally serving is seen as ‘doing’ something for someone else. But often, even though we may not admit it, the thing we’re doing can be as much for ourselves as for the other person: have you ever given a massage because you hoped to get one in return; or done something for someone in order to store up goodwill for the future, or even get approval from them?

This kind of ‘conditional helping’ can cause problems if the other person doesn’t actually want what we’re offering – and we can end up feeling offended, or rejected.

So learning how to wholeheartedly put aside what we want and serve ‘cleanly’ for the other person is crucial if the interaction is going work for both.

We may get our own pleasure out of the exchange (or it may just be a neutral experience), but being clear that what we’re doing is for them, and that it’s something they want and agree to (as well – of course – as being something we’re willing to give) is fundamental to genuinely being of service.

TAKING – I wrap myself around you, my arms taking the hug I need. I am doing what I want.

One thing that really helps us to be able to serve cleanly is to know clearly what we do want for ourselves – so we can then choose to set it aside, for the benefit of the other person. And one of the best ways to learn what we want is by learning how to take consentingly.

Taking often feels like a dirty word – associated with invasive or aggressive behaviour; it’s become synonymous with stealing and the abuse of power, the logical conclusion of which is rape and war. But those are the kinds of taking that happen when the boundaries of consent are being transgressed.

If we get agreement from the person who’s giving us something, taking can actually be a very healthy thing: identifying, and looking after our own needs, and nourishing ourselves by listening to and responding to our desires.

The trouble is most of us don’t know what we truly want for ourselves. We’ve learned to filter our ideas of what we want based on expectations of what we’ve been told we ‘should’ or ‘ought’ to want, or what’s ‘normal’.

ALLOWING – I allow you to put your arms around me. I am doing what you want.

One reason a lot of us find the concept of taking so challenging is that when it’s un-consenting it results in someone being forced to allow. And we all know only too well how that feels.

Every day we are forced into allowing: enduring endless ads for things we don’t want (even on our phones and in our homes); tolerating behaviour from strangers, colleagues and even friends, which doesn’t take into account our own needs.

Allowing is something we’ve learned since the day we were born. Our earliest experiences as a baby are ones of allowing our caregivers to make decisions about what happens to our body. They may have our own best interests at heart, but even if we cry or scream because we don’t like something they’re doing, our protest is often overridden. So we learn to put up and shut up.

In fact most of us have become so used to over-riding our own needs that we no longer know what our limits really are. We no longer know when to say ‘this far but no further’. Often until it’s too late.

But when we can be clear about what we do want for ourselves, it becomes much easier to know where our boundaries and limits are, and how to maintain them.

And when we are truly in choice about what we allow – particularly in interaction with other people – allowing then becomes a gift: the gift of access to you, on your own terms.

ACCEPTING – I accept your arms around me so you can hold me just the way I like it. You are doing what I want.

When we know what we want (as opposed to what we think others might want us to want) it makes it much easier for us to be able to ask for, and accept it.

If you were offered the chance to be touched in the way which would feel most exquisite to you right now – not just a “well I guess that would be OK”, but a real “ohhhh yeahhhhh I’d love that!” – would you know what that was, or feel able to ask for it?

Even just thinking about it, you might notice some doubts, or qualifiers creeping in:

- Should I ask for something they’ll be comfortable with?

- What if they think what I ask for is stupid?

- What if they say no to my request?

- What if they say yes, and then I end up actually getting what I want?

It can often feel awkward to accept a gift without any need to give something in return. We worry we might be being selfish. But accepting a no-strings gift – as challenging as that can be – is probably one of the best ways to achieve a feeling of self-worth and self-acceptance.

Getting the chance to spend time receiving a gift that is for us alone, having someone else completely put their desire aside and attend to ours, can be immensely healing.

It’s best to be prepared

Training your consent muscles by learning how it feels to consciously engage with these four different types of interaction, can help build foundations for the kind of healthy relationships and intimacy we seek as LGBT+ people, moving away from the damaging patterns that many of us have had to overcome in order to be ourselves.

It all comes down to knowing what you want.

Having this awareness also helps shed light on some of our more shadowy behaviours – what happens when we don’t feel able to ask for what we want, and the things we do instead to get our needs met. If we can notice these when they pop up (as well as recognising them in others) then we have the choice to change.

Of course humans, being the complex, imperfect, creative, creatures we are, there are no quick fixes with this stuff, there are always more paths to explore, and the terrain can sometimes be bumpy – but when you’re on a journey it’s definitely helpful to have a compass or map!

Michael Dresser is an Embodied Intimacy Coach, and certified Wheel Of Consent workshop facilitator, offering safe, gentle, and engaging learning environments with choice and the needs of the individual at the centre. Based in Moray, he works with individuals, couples and groups, and runs workshops in Scotland, London, and across the UK.